Let’s scan through ten (at times competing) notions of “Jewish Music” that have emerged during the last, well, 500 years.

Background information for this is in the articles by Philip Bohlman and Edwin Seroussi listed in the Syllabus (they were last week’s assignments, so I’m absolutely positive that everyone has already read them carefully…). These studies are also reflected in this week’s reading, and especially the “Jewish Music” entry in Oxford Music Online, which opens with the following statements.

‘Jewish music’ as a concept emerged among Jewish scholars and musicians only in the mid-19th century with the rise of modern national consciousness among European Jews, and since then all attempts to define it have faced many difficulties. The term ‘Jewish music’ in its nation-oriented sense was first coined by German or German-trained Jewish scholars, among whom the most influential in this respect was A.Z. Idelsohn (1882–1938), whose book Jewish Music in its Historical Development (1929) was a landmark in its field that is still widely consulted today . Idelsohn was the first scholar to incorporate the Jewish ‘Orient’ into his research, and thus his work presents the first ecumenical, though still fragmentary, description of the variety of surviving Jewish musical cultures set within a single historical narrative. In his work Idelsohn pursued a particular ideological agenda: he adopted the idea of the underlying cultural unity of the Jewish people despite their millenary dispersion among the nations, and promoted the view that the music of the various Jewish communities in the present expresses aspects of that unity. Moreover, Idelsohn’s work implied a unilinear history of Jewish music dating back to the Temple in biblical Jerusalem. This approach was perpetuated in later attempts to write a comprehensive overview of Jewish music from a historical perspective (e.g. Avenary, 1971–2). Despite its problematic nature, the concept of ‘Jewish music’ in its Idelsohnian sense is a figure of speech widely employed today, being used in many different contexts of musical activity: recorded popular music, art music composition, printed anthologies, scholarly research and so on. The use of this term to refer both to the traditional music of all Jewish communities, past and present, and to new contemporary music created by Jews with ethnic or national agendas is thus convenient, as long as its historical background and ideological connotations are borne in mind.

Below, I’m scanning through some of the connections that “Jewish music” elicits. I’m not pretending to be exhaustive, and I’m also having some fun in choosing related visual and musical examples to make my points.

1. Jewish music as “Musica Haebreorum”: the notion of a “music of the Hebrews (the Jews)” really begins with Christian Humanists and their heirs.

An example I particularly like (also because it has been eminently understudied, so far), and that one can read online, is from Ercole Bottrigari, Il trimerone de’ fondamenti armonici, ouero lo essercitio musicale, giornata terza, 1599 (Source: Bologna, Civico Museo Bibliografico Musicale, MS B44, 1-23): Bottrigari specifically addresses “il Canto degli Hebrej” (the song of the Jews) and the musical rendition of the “masoretic accents” that govern the singing of the Hebrew Bible in synagogue liturgy. (Image source).

2. Jewish (musical) antiquity. But whose antiquity really is it?

Venetian composer Benedetto Marcello, and many many more after him, searched for “Jewish musical antiquity.” (You can read more about this topic here).

See a contemporary incarnation of the belief in Jewish musical antiquity by Jordi Savall-Hespèrion XXI, Lavava y suspirava (romance) (Anónimo Sefardí):

3. The Wissenschaft des Judentums (19th cent.) and the invention of “Jewish Music” as a Jewish notion

An interesting byproduct of 19th-century Jewish scholarship was been the construction of the “Italian Jewish Renaissance” as a golden age of musical production, and of Jewish music as “art music.” Listen below to Salamone Rossi, ‘al naharot bavel (Psalm 137), by The Prophets of the Perfect Fifth (I profeti della quinta)

4. Jewish music as “Music of the Jewish People” (with the related notions of Nationalism & Identity), as found in the “St. Petersburg Society for Jewish Folk Music” and in related Zionist musical agendas.

Lazare Saminsky (Odessa 1882- NY 1959), composed Conte Hebräique (Hebrew Fairy Tale) in Palestine in 1919, en route from Russia to America (via the UK).

5. Jewish music as “Judaism in Music” (an expression made quite popular by Richard Wagner in an eponymous antisemitic pamphlet published in 1850 and periodically reassessed) brings with it a certain passion for singling out “the Jewish elements” in the music of eminent composers of Jewish descent.

This is a trademark of many 20th-century scholarly contribution to the field.

An excellent summary on the relationship between Wagner and modern Jewish sensibilities can be found in the form of a satire in Curb Your Enthusiasm, Season 2, Episode 3: Trick or Treat (October 7, 2001) (note when Larry David whistles “Springtime from Hitler” from the Producers).

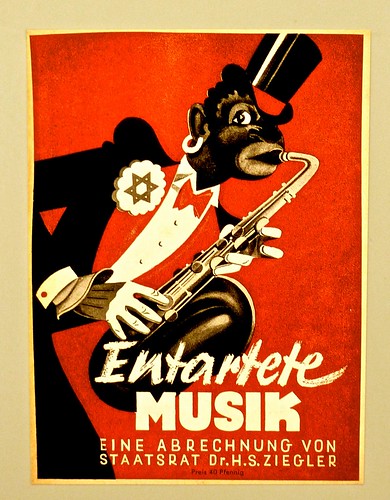

6. Jewish music as “Degenerate Music/Art” and the passion of making lists of “Jewish” composers, compositions, etc., so that music can be purified from their influence. This takes the previous notion a step (or two, or 10,000) further.

And, well, this is what the Nazis tried to do…

Watch “Illinois Nazis” enjoying their right to free speech in John Landis, The Blues Brothers (USA 1980):

A book published in Nazi Germany, listing Jewish music professionals, is included in the music holdings of The Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life, and will be accessible to interested students as soon as these holdings are transferred to our new facility.

7. Jewish music as lost (or suppressed) music: in the view of post-Holocaust cultural agendas, any sample of Jewish culture is worthy of attention, and the enormity of the historical legacy of the Holocaust trumps any aesthetic consideration.

Watch, for example, this news report on Francesco Lotoro’s KZ Musik project, conducted with the support of the European Union:

8. Jewish music as revival.

A step further from recovering a lost musical world is reviving it.

In her essay, Sounds of Sensibility (1998), Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett outlines several implications related to the (American) revival of “Klezmer” music. A haunting parallel drawn by BKG is that of the revivalist as necromancer, aka, someone who brings the dead back to life. But revivalism means, first and foremost, re-thinking “tradition.” However posited, such as stance is invariably close to cultural subversion.

In his fascinating eulogy of Adrienne Cooper (1946-2011), one of the protagonists of the American revival of Ashkenazi culture, Canadian writer, Michael Wex, thus articulated the special relationship that late 20th-century Jewish revivalists had with tradition:

[Adrienne Cooper] had a talent for subversion along with an innate sense of decorum that let her reverse a tradition, turn it inside out, before any of its guardians had actually noticed.

The New-York band, Klezmatics, turned the socialist Yiddish song, Ale brider into an anthem for Queer rights:

9. Jewish music as “soul” and “fusion” (or, how to market Jewish culture to the “masses”).

A way to translate the idea of “musics in contacts” that characterizes Jewish culture into the musical market is to present it as either soul or fusion.

An example by Argentinian-Israeli musician, Giora Feidman highlights a musical aesthetics based on soulfulness:

10. Jewish music as “world music” (or “ethnic music”) (or, how to market Jewish culture to the “elites”)

By categorizing “Jewish music” as “world music,” one can find a legitimized place for it within the music market. Until not too long ago, one could find Jewish music within the “world music” sections of stores like Tower Records. With the digital revolution, descriptive metadata (on platforms like iTunes, Amazon Music, Pandora, Spotify, Soundcloud, etc.) is king.

An example by Moroccan-Israeli cantor and singer, Emil Zrihan, who made the “leap” from Israeli synagogue cantor and pop star to “ethnic voice” (check out the arrangement of the Arab-Andalusian melody set to the Hebrew religious poem Kochav Tzedeq below):