In Israeli songs and poetry in Hebrew, San Francisco and its Bay are often presented as a distant and pleasant place, which causes poets and songwriters to reflect on their land (or love) of origin. San Francisco seems to orient the perception of Israel in Hebrew lyrics.

The similarity of facing West (the Mediterranean Sea, and the Pacific Ocean, respectively), indeed seems to prompt some unexpected connections, which are also reflected in the Jewish musical history that unites Israel to the Bay Area.

There are all kinds of wine houses, taverns and dives

In San Francisco, San Malo and Marseille….

There are blondes and brunettes that will eat you alive!

All waiting for some “beau” to sweep them away…

But as for me, despite it all, I swear sincerely,

I am chained down to some dilapidated dame..

If my harmonica sings out a weepy blues,

And if I hate myself, it’s not the wine or booze,

It’s that female, damn it, she’s the one to blame!What’s come over me? The devil knows!

I am feeling confused and dazed…

Is it the night? Or is it this song

That has left me bewitched and amazed?

A harmonica spreads its wings in flight!

Singing a song of laughter and woes

oh good lord, will you explain the night?

Or is it only the devil that knows?

(Edna Goren and Kobi Recht, Zemer mapuchit, or “The Song of the Harmonica,” 1968; lyrics by Nathan Alterman and music by Sasha Argov, 1956; Hebrew lyrics found here, and English translation, by Achinoam Nini/Noa, available here).

Sitting in San Francisco by the Water

Carried away by the blues and greens

It’s beautiful in San Francisco by the Water

Then why do I feel so removedWatching the ducks, roaming amongst the boats

and the Golden Gate Bridge, beautiful like in a movie

It’s a shame you’re not here

With me to see it

You’d say you’d never leaveI watch Doctor J, tear down the nets

and Kareem Abdul Jabbar, touches the sky

It’s a shame you’re not here

With me to see it

It’s so beautiful in San Francisco by the WaterSuddenly I want to go back home

Return to the swamp

To sit in Kasit with Moshe and Chatske

Give me Mount Tibor

Give me the Kinneret

I love and keep falling in love with my little Israel Warm and Charming

(Arik Einstein, san fransisqo ‘al ha-mayim – San Francisco on the Water, from the album Hamush bemishkafaim – Armed With Glasses, 1980; lyrics found here).

This week, we explore a host of musical relations between Israel and the San Francisco Bay Area.

A Hebrew poem by Yehuda Amichai (1924-2000), Israel’s leading poet, dedicated verses to San Francisco and the Bay Area. (The English translation that appears below was done by Avshalom Guissin, and can be found here; a UC Press edition of translations of Amichai’s poems, by Chana Bloch and Stephen Mitchell, is linked here; thank you to my friend Dorothy Richman for sharing this poem with me).

North of San Francisco*

Here the soft hills touch the sea,

like eternity touching on eternity.

And the cows that graze on them

ignore us, like angels.

Even the scent of ripe cantaloupe in the cellar

is a prophecy of calm.The darkness does not fight the light

but passes it forward

to another light and the only pain

is the pain of not staying.In my land called holy

eternity isn’t allowed to be eternity:

they divided it into small religions

and demarcated it in deified departments

and shattered it into shards of history

sharp and mortally wounding.

And they turned its calm reaches

into a closeness that twitches with present pain.On Bolinas beach at the bottom of the wooden stairs

I saw bare buttocked girls

bowing down in the sand

intoxicated with the kingdom of everlasting kingdoms,

and their souls within like doors

closing and opening,

closing and opening,

to the rhythm of the breaking waves.* From: Yehuda Amichai, Me-Adam Bata, Ve-El Adam Tashuv (Schocken Publishing, Tel Aviv, 1985), pp. 99–100.

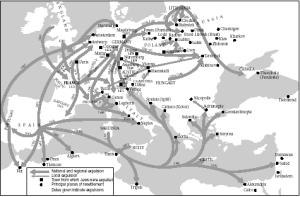

The history of the musical relations between Israel and the Bay Area go back to the 1930’s, when San Francisco’s became the first Jewish community in the Diaspora to raise funds for the founding of the Palestine Orchestra (which, as we have learned in a previous week, was the ancestor of modern day’s Israeli Philharmonic Orchestra).

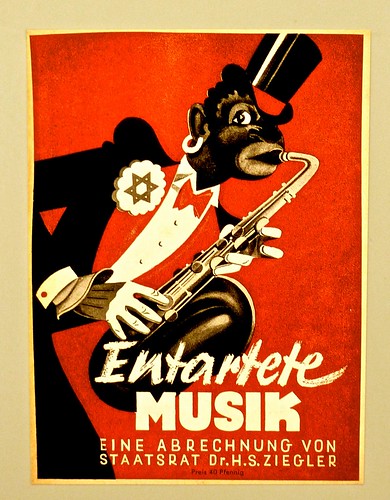

The film, Orchestra of Exiles (2012), about the creation of the Palestine Orchestra by Polish violinist Bronislaw Huberman, was indeed included in our Syllabus this semester.

The fundraising for the Palestine Orchestra, and the later commissioning of music to Israeli composers such as Paul Ben-Haim (1897-1984) and Marc Lavry (1903-1967), was the work of Reuben R. Rinder (1887-1966), who between 1913 and 1962 served as the Cantor of Congregation Emanu-El in San Francisco.

The Western Jewish Americana archives of The Magnes, accessible at The Bancroft Library, include the Reuben Rinder’s papers, a selection of which is available in an online narrative format (created by your instructor…). You can check it out here.

Several decades later, the musical ties between the Bay Area and Israel were renewed, when a San-Francisco-summer-of-love Jewish phenomenon, the music of the House of Love and Prayer (a Jewish center founded in San Francisco in 1967, also documented in the Western Jewish Americana archives of The Magnes at The Bancroft Library (link here), was transplanted to Israel along with its creator, Shlomo Carlebach (1925-1994).

Interestingly enough, Congregation Emanu-El and the House of Love and Prayer were located a few blocks from one another. See Google Maps directions for this 5-minute walk through San Francisco’s Jewish musical history.

Carlebach (who was born in Berlin), had studied in New York, and had moved to the Bay Area in 1966, as an emissary of the Habad movement, along with Zalman Schachter, as detailed in this week’s reading assignment, eventually moved to Israel, after one of his songs won the Hassidic Song Festival, one of the many song contests created in Israel after the festival hazemer hayisraeli that we discussed last week.

Here’s a clip from an Israeli television broadcast of Carlebach (1973).

A more recent, and less explored connection between our Bay and the Israeli musical scene, is in the open-source-inspired creation of the website, An Invitation to Piyyut (as we’ve learned, a piyyut is a Hebrew poem included in synagogue liturgy).

This extraordinary resource (which is connected to a real-life cultural initiative, Kehillot Sharot, or “singing communities” (active across Israel in transmitting traditional liturgical-musical lore to new generations, defying the boundaries between religion, art, culture, gender, and religious affiliations) charts century-old Hebrew poems in their musical versions across the Jewish Diaspora through texts and melodies. These resources are fully searchable, and also organized according to several principles, such as author, religious occasion (liturgical and para-liturgical events, life cycle ceremonies), and Jewish culture of origin. For example, if you follow this link, you will land on a page listing 21 different poems for the upcoming festival of Hanukkah, in countless musical versions spanning the entire Jewish Diaspora.

The website exists though the efforts of Israeli musician and music promoter (and Music in Israel “Zoom guest” this semester) Yair Harel (and the formidable support of the Avi Chai Foundation. You can see Yair in action while presenting his project in a very US-minded, Bay-Area-familiar, setting, here:

![[2017.5.1.196] (The Jewish Plot to Survive) "I just tell the Americans that they are communists, and to the Russians that they are fascists..."](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/48993329071_72637fd2fa_z.jpg)